Thingiverse

Tea Caddy Used at Edenton Tea Party in 1774 by smlee

by Thingiverse

Last crawled date: 2 years, 12 months ago

Tea Caddy from the Edenton Tea Party

=============================

What is the significance of a drink? Drinks serve as an anchor for social gatherings. In colonial America the most important drink was tea. Social occasions in the colonies, like in the motherland, tended to center around tea and teatime.[1] Like the English, colonists took their tea drinking seriously, consuming great quantities in much of the same fashion as modern Americans drink coffee. Two main forces competed in the tea market: the British East India Tea Company and the Dutch East India Company. Originally, the British East India Tea Company monopolized the market; however, the Dutch traders “captured much of the colonial market by offering lower prices.”[2] The British East India Tea Company floundered under Dutch competition and appealed to Parliament for help in 1773. Several leading members of Parliament were invested in the British East India Tea Company, and they wanted to ensure their company would become “more attractive to the colonial market.” This resulted in a bailout known as the Tea Act of 1773, which “allowed the company to eliminate the English merchant middleman and sell directly to the colonists. Even with the tax still in effect, English tea would now be cheaper than its competitor.”[3]

The colonists interpreted the Tea Act as “an excuse to collect the tax on tea and thus establish a precedent for new taxes on British goods.”[4] Americans loved their tea, but they believed that the new taxes on British goods, like tea and cloth, were an infringement on their rights as citizens of the British Empire. In the colonies, tea symbolized Parliament’s belief that it could levy taxes without considering its constituents’ wants and needs. Many thought that by abstaining from their tea drinking habits, they were standing up for their right to have representation in Parliament. This abstention became almost mandatory for patriots.[5] Although many Americans are familiar with revolts and political protests led by men in the years leading up to the American Revolution–namely the Boston Tea Party–some Americans are woefully unaware of their foremother’s political actions in the pre-Revolutionary years of the country.[6] Women and men both actively participated in political protest. In fact, some three hundred women swore to give up imported British tea in the Boston area almost three years before the Sons of Liberty even thought about throwing a single bag of tea into their harbor![7]

Colonial women’s primary sphere of influence was domestic. They were responsible for obtaining clothes for their families and putting food in their pantries. Because of this, harsh taxes on imported goods, especially those created by the Tea Act, landed squarely in the hands of colonial women, making the tea boycott a women’s cause.[8] Male leaders in South Carolina, specifically Presbyterian minister William Tennent III, called upon women to save the colonies “from the Dagger of Tyranny” by giving up tea, which in turn became a test of colonial patriotism.[9] They created anti-tea leagues, social groups that supported the tea boycott, and even experimented with brewing “liberty teas” from local leaves like strawberries, sage, sassafras, and raspberries.[10] Women across the colonies took up the cause, and reports of their political actions increased exponentially following the passing of the Tea Act in 1773. Newspapers carried letters from different anti-tea leagues to other groups, encouraging them to stay strong in their abstention.[11] Even children understood the severity of the matter. One story speaks of a nine year old girl, Susan Boudinot, in New Jersey who politely took a cup of tea from the New Jersey governor at the time, curtsied, and then threw it out the window.[12]

Women were so outspoken in their anti-tea leagues and political activities, that even popular culture encouraged them to continue sticking it to the British. The following excerpt from a poem encouraged women to carry on with their political activities:

“Throw aside your Bohea and your Green Hyson tea

And all things with a new-fashion duty;

Procure a good store of the choice Labrador[e]

For there’ll soon be enough here to suit ye;

These do without fear, and to all you’ll appear

Fair, charming, true, lovely, and clever,

Tho’ the times remain darkish, young men may be sparkish,

And love you much stronger than ever.”[13]

Sources tell us about women in Wilmington, North Carolina, walking in an orderly and somber mood to burn their imported tea, but the most well-known of women’s anti-tea actions in the colonies during this time was the Edenton Tea Act.[14] Ten months after the famous Boston Tea Party, on October 25, 1774, fifty-one women gathered in Edenton, North Carolina, at the home of Elizabeth King to form the Edenton Ladies’ Patriotic Guild.[15] The organization of the guild was supposedly headed by Penelope Pagett Barker, a spirited woman and fervent patriot whom stories say earned the respect of British soldiers in later years when she used her husband’s sword to cut the reins out of the hands of a British soldier who was attempting to steal her horses.[16] The Guild composed and signed “an agreement to boycott all British-made goods and products.”[17] The only surviving text from this declaration comes from reprintings of it in British newspapers of the time.[18] The British thought little of women’s political involvement in the colonies and printed the declaration alongside a political cartoon that mocked the Edenton women by portraying them as incredibly masculine and ridiculous. It is from this cartoon that the nickname “Edenton Tea Party” arose–mostly as a way to mock the participants.[19]

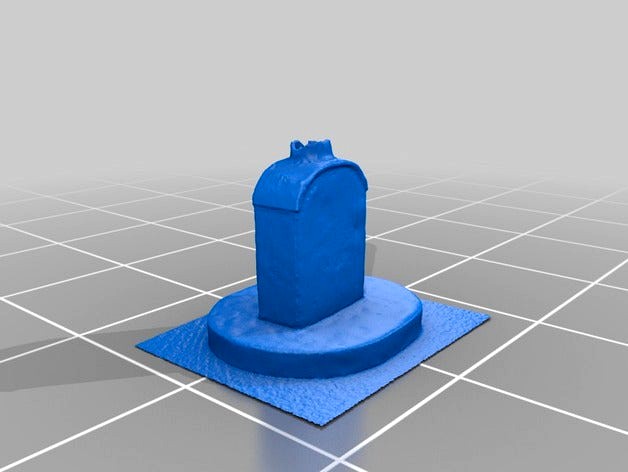

The tea caddy in the collections of the North Carolina Museum of History (Accession # H.1914.187.1) is believed to be from this gathering of politically-minded women. One can almost imagine Barker, King, and the other forty-nine women using this caddy to store raspberry, red-root bush, or sassafras leaves for brewing liberty tea during the meeting. Today, visitors can see the home of Penelope Barker, which now serves as a tribute to the Guild’s work in 1774. A large bronze teapot atop a Revolutionary War cannon also sits in Courthouse Square in Edenton to memorialize the importance of the Edenton Tea Party.

If the tea caddy is truly from the Edenton tea party, we can analyze this material culture and compare it to other material culture of the Edenton area related to the Edenton tea party to reveal demographic information about the women of the tea party. The tea caddy is porcelain and could be an English ware or a Chinese ware. English wares were “decorated in underglaze blue, overglaze enamels, and overglaze transfer printed patterns.” It is difficult to tell if the pattern is hand painted or transfer printed. Chinese wares are hand painted and there would be small defects in the pattern, transfer prints are perfect and are English ware.[20] An educated guess would pinpoint the tea caddy as hand painted, and thus Chinese ware. Porcelain was used in many tablewares indicating it was a commonly acquired good and a person did not have to be wealthy to own it. As mentioned above, Penelope Barker’s house still exists and is a historic site, but the house was developed in the 1830s three times its original size. The original house was not on the riverfront and it consisted of only “a parlor wing and half hall built in a Federal style.”[21] Therefore we can surmise Penelope Barker’s home was the typical modest colonial home. From the analysis of the material culture and the house, historians can make an educated guess that the women who participated in the Edenton Tea Party were not wealthy, but regular members of society.

About the 3D Model

To create the 3D image of the Tea Caddy, our team used 123D Catch, an application produced by Autodesk. 123D Catch converts ordinary photos in 3D models. 123D Catch is a free application and objects are stored and made accessible on the cloud. Our team photographed the Tea Caddy thirty-five times at different angles using an iPhone 6. The 123D Catch app then melded the photos together and saved it on the cloud. After downloading the image from the 123D Catch web app, we deleted extraneous data using MeshLab, a free software program. We then proceeded to use netfabb Basic to clean up the item and give it a flat bottom.

View another 3D model (with color) made with 123D Catch.

About the Object

North Carolina Museum of History

Accession #: H.1914.187.1

Date: 1774

Place: Edenton, Chowan, North Carolina, USA

Dimensions: [Lt] [Wdt]3 11/16" [Ht]5 5/16" [Dt]1 3/4"

Materials: Porcelain

Secondary Sources

Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Claghorn, Charles E. Women Patriots of the American Revolution: A Biographical Dictionary. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1991.

Copeland, David A. Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2000. http://ebooks.abc-clio.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313007262&id=20005CCD-327.

DePauw, Linda Grant. Founding Mothers: Women in America in the Revolutionary Era. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975.

Diagnositic Artifacts in Maryland. “Decoration, Procelain.” Last modified December 30, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2014. http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/Porcelain.html.

“The Edenton ‘Tea Party’.” Learn NC, last modified 2009. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-revolution/4234#comment-1099.

Gundersen, Joan R. To Be Useful to the World: Women in Revolutionary America, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

North Carolina History Project. “Barker House.” Accessed November 3, 2014. http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/475/entry.

Endnotes

[1] Linda Grant DePauw, Founding Mothers: Women in America in the Revolutionary Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975), 156.

[2] Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 20.

[3] Ibid, 20.

[4] Ibid, 20.

[5] DePauw, 155.

[6] “Sons of Liberty,” Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum: A Revolutionary Experience, accessed October 30, 2014, http://www.bostonteapartyship.com/sons-of-liberty.

[7] David A. Copeland, Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2000), http://ebooks.abc-clio.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313007262&id=20005CCD-327, 317.

[8] DePauw, 156.

[9] Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers, 21.

[10] DePauw, 156.

[11] DePauw, 157.

[12] Joan R. Gundersen, To Be Useful to the World: Women in Revolutionary America, 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 175.

[13] DePauw, 157.

[14] Gundersen, 174.

[15] Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 21.

[16] Charles E. Claghorn, Women Patriots of the American Revolution: A Biographical Dictionary (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1991) 19.

[17] Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers, 21.

[18] “The Edenton ‘Tea Party’.” Learn NC, last modified 2009. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-revolution/4234#comment-1099.

[19] DePauw, 159.

[20] “Decoration, Procelain,” Diagnositic Artifacts in Maryland, last modified December 30, 2012, accessed November 3, 2014, http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/Porcelain.html.

[21] “Barker House,” North Carolina History Project, accessed November 3, 2014, http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/475/entry.

=============================

What is the significance of a drink? Drinks serve as an anchor for social gatherings. In colonial America the most important drink was tea. Social occasions in the colonies, like in the motherland, tended to center around tea and teatime.[1] Like the English, colonists took their tea drinking seriously, consuming great quantities in much of the same fashion as modern Americans drink coffee. Two main forces competed in the tea market: the British East India Tea Company and the Dutch East India Company. Originally, the British East India Tea Company monopolized the market; however, the Dutch traders “captured much of the colonial market by offering lower prices.”[2] The British East India Tea Company floundered under Dutch competition and appealed to Parliament for help in 1773. Several leading members of Parliament were invested in the British East India Tea Company, and they wanted to ensure their company would become “more attractive to the colonial market.” This resulted in a bailout known as the Tea Act of 1773, which “allowed the company to eliminate the English merchant middleman and sell directly to the colonists. Even with the tax still in effect, English tea would now be cheaper than its competitor.”[3]

The colonists interpreted the Tea Act as “an excuse to collect the tax on tea and thus establish a precedent for new taxes on British goods.”[4] Americans loved their tea, but they believed that the new taxes on British goods, like tea and cloth, were an infringement on their rights as citizens of the British Empire. In the colonies, tea symbolized Parliament’s belief that it could levy taxes without considering its constituents’ wants and needs. Many thought that by abstaining from their tea drinking habits, they were standing up for their right to have representation in Parliament. This abstention became almost mandatory for patriots.[5] Although many Americans are familiar with revolts and political protests led by men in the years leading up to the American Revolution–namely the Boston Tea Party–some Americans are woefully unaware of their foremother’s political actions in the pre-Revolutionary years of the country.[6] Women and men both actively participated in political protest. In fact, some three hundred women swore to give up imported British tea in the Boston area almost three years before the Sons of Liberty even thought about throwing a single bag of tea into their harbor![7]

Colonial women’s primary sphere of influence was domestic. They were responsible for obtaining clothes for their families and putting food in their pantries. Because of this, harsh taxes on imported goods, especially those created by the Tea Act, landed squarely in the hands of colonial women, making the tea boycott a women’s cause.[8] Male leaders in South Carolina, specifically Presbyterian minister William Tennent III, called upon women to save the colonies “from the Dagger of Tyranny” by giving up tea, which in turn became a test of colonial patriotism.[9] They created anti-tea leagues, social groups that supported the tea boycott, and even experimented with brewing “liberty teas” from local leaves like strawberries, sage, sassafras, and raspberries.[10] Women across the colonies took up the cause, and reports of their political actions increased exponentially following the passing of the Tea Act in 1773. Newspapers carried letters from different anti-tea leagues to other groups, encouraging them to stay strong in their abstention.[11] Even children understood the severity of the matter. One story speaks of a nine year old girl, Susan Boudinot, in New Jersey who politely took a cup of tea from the New Jersey governor at the time, curtsied, and then threw it out the window.[12]

Women were so outspoken in their anti-tea leagues and political activities, that even popular culture encouraged them to continue sticking it to the British. The following excerpt from a poem encouraged women to carry on with their political activities:

“Throw aside your Bohea and your Green Hyson tea

And all things with a new-fashion duty;

Procure a good store of the choice Labrador[e]

For there’ll soon be enough here to suit ye;

These do without fear, and to all you’ll appear

Fair, charming, true, lovely, and clever,

Tho’ the times remain darkish, young men may be sparkish,

And love you much stronger than ever.”[13]

Sources tell us about women in Wilmington, North Carolina, walking in an orderly and somber mood to burn their imported tea, but the most well-known of women’s anti-tea actions in the colonies during this time was the Edenton Tea Act.[14] Ten months after the famous Boston Tea Party, on October 25, 1774, fifty-one women gathered in Edenton, North Carolina, at the home of Elizabeth King to form the Edenton Ladies’ Patriotic Guild.[15] The organization of the guild was supposedly headed by Penelope Pagett Barker, a spirited woman and fervent patriot whom stories say earned the respect of British soldiers in later years when she used her husband’s sword to cut the reins out of the hands of a British soldier who was attempting to steal her horses.[16] The Guild composed and signed “an agreement to boycott all British-made goods and products.”[17] The only surviving text from this declaration comes from reprintings of it in British newspapers of the time.[18] The British thought little of women’s political involvement in the colonies and printed the declaration alongside a political cartoon that mocked the Edenton women by portraying them as incredibly masculine and ridiculous. It is from this cartoon that the nickname “Edenton Tea Party” arose–mostly as a way to mock the participants.[19]

The tea caddy in the collections of the North Carolina Museum of History (Accession # H.1914.187.1) is believed to be from this gathering of politically-minded women. One can almost imagine Barker, King, and the other forty-nine women using this caddy to store raspberry, red-root bush, or sassafras leaves for brewing liberty tea during the meeting. Today, visitors can see the home of Penelope Barker, which now serves as a tribute to the Guild’s work in 1774. A large bronze teapot atop a Revolutionary War cannon also sits in Courthouse Square in Edenton to memorialize the importance of the Edenton Tea Party.

If the tea caddy is truly from the Edenton tea party, we can analyze this material culture and compare it to other material culture of the Edenton area related to the Edenton tea party to reveal demographic information about the women of the tea party. The tea caddy is porcelain and could be an English ware or a Chinese ware. English wares were “decorated in underglaze blue, overglaze enamels, and overglaze transfer printed patterns.” It is difficult to tell if the pattern is hand painted or transfer printed. Chinese wares are hand painted and there would be small defects in the pattern, transfer prints are perfect and are English ware.[20] An educated guess would pinpoint the tea caddy as hand painted, and thus Chinese ware. Porcelain was used in many tablewares indicating it was a commonly acquired good and a person did not have to be wealthy to own it. As mentioned above, Penelope Barker’s house still exists and is a historic site, but the house was developed in the 1830s three times its original size. The original house was not on the riverfront and it consisted of only “a parlor wing and half hall built in a Federal style.”[21] Therefore we can surmise Penelope Barker’s home was the typical modest colonial home. From the analysis of the material culture and the house, historians can make an educated guess that the women who participated in the Edenton Tea Party were not wealthy, but regular members of society.

About the 3D Model

To create the 3D image of the Tea Caddy, our team used 123D Catch, an application produced by Autodesk. 123D Catch converts ordinary photos in 3D models. 123D Catch is a free application and objects are stored and made accessible on the cloud. Our team photographed the Tea Caddy thirty-five times at different angles using an iPhone 6. The 123D Catch app then melded the photos together and saved it on the cloud. After downloading the image from the 123D Catch web app, we deleted extraneous data using MeshLab, a free software program. We then proceeded to use netfabb Basic to clean up the item and give it a flat bottom.

View another 3D model (with color) made with 123D Catch.

About the Object

North Carolina Museum of History

Accession #: H.1914.187.1

Date: 1774

Place: Edenton, Chowan, North Carolina, USA

Dimensions: [Lt] [Wdt]3 11/16" [Ht]5 5/16" [Dt]1 3/4"

Materials: Porcelain

Secondary Sources

Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Claghorn, Charles E. Women Patriots of the American Revolution: A Biographical Dictionary. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1991.

Copeland, David A. Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2000. http://ebooks.abc-clio.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313007262&id=20005CCD-327.

DePauw, Linda Grant. Founding Mothers: Women in America in the Revolutionary Era. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975.

Diagnositic Artifacts in Maryland. “Decoration, Procelain.” Last modified December 30, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2014. http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/Porcelain.html.

“The Edenton ‘Tea Party’.” Learn NC, last modified 2009. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-revolution/4234#comment-1099.

Gundersen, Joan R. To Be Useful to the World: Women in Revolutionary America, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

North Carolina History Project. “Barker House.” Accessed November 3, 2014. http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/475/entry.

Endnotes

[1] Linda Grant DePauw, Founding Mothers: Women in America in the Revolutionary Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975), 156.

[2] Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 20.

[3] Ibid, 20.

[4] Ibid, 20.

[5] DePauw, 155.

[6] “Sons of Liberty,” Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum: A Revolutionary Experience, accessed October 30, 2014, http://www.bostonteapartyship.com/sons-of-liberty.

[7] David A. Copeland, Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2000), http://ebooks.abc-clio.com.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313007262&id=20005CCD-327, 317.

[8] DePauw, 156.

[9] Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers, 21.

[10] DePauw, 156.

[11] DePauw, 157.

[12] Joan R. Gundersen, To Be Useful to the World: Women in Revolutionary America, 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 175.

[13] DePauw, 157.

[14] Gundersen, 174.

[15] Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America’s Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 21.

[16] Charles E. Claghorn, Women Patriots of the American Revolution: A Biographical Dictionary (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1991) 19.

[17] Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers, 21.

[18] “The Edenton ‘Tea Party’.” Learn NC, last modified 2009. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-revolution/4234#comment-1099.

[19] DePauw, 159.

[20] “Decoration, Procelain,” Diagnositic Artifacts in Maryland, last modified December 30, 2012, accessed November 3, 2014, http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/Porcelain.html.

[21] “Barker House,” North Carolina History Project, accessed November 3, 2014, http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/475/entry.

Similar models

thingiverse

free

Tea Caddy used at the Edenton Tea Party in 1774 by hrmoll13

...e: edenton, chowan, north carolina, usa

dimensions: [lt] [wdt]3 11/16" [ht]5 5/16" [dt]1 3/4"

materials: porcelain

3dwarehouse

free

American Revolutionary War

...ber 3rd, 1783). continental army vs. the british brigade and american soldier vs. the royal infantry like yankee doodle. #patriot

3dwarehouse

free

Prentis Store

...as created with the aid of drawings from the habs colonial williamsburg survey of 1976. #brick_building #colonial #prentis #store

3dwarehouse

free

American Patriots Party

...patriots party

3dwarehouse

2d and 3d versions of the american patriots party symbol. american patriots party app donald j. trump

3dwarehouse

free

Flag of North Borneo (1948-1963)

...northeast of the island of borneo, correspondingly to the current state of sabah, part of malaysia. #british #flag #borneo #north

turbosquid

$40

North Carolina Political Map

...orth carolina political map for download as 3ds, max, and obj on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1302430)

3dwarehouse

free

Battle of New Orleans

...), the buccaneer, during battle in louisiana with fog appears, on the 8th to 26th of january 1815 to put an end of this conflict.

thingiverse

free

Roman Sacrifice by Walker

...oman sacrifice by walker

thingiverse

roman sculpture from the british museum, greek and roman life room.

created with 123d catch

clara_io

free

Boston Tea Party

...boston tea party

clara.io

cg_trader

$40

North Carolina Political Map

...w carolina. features every county in the state. the modifier stack is uncollapsed allowing for easy change of extrusion settings.

Smlee

thingiverse

free

19th-Century Hog Scraper by smlee

...ity’s library website.

us epa agi pork production. accessed october 22, 2014. http://www.epa.gov/oecaagct/ag101/printpork.html.

thingiverse

free

18th Century Butter Print: by smlee

....

[5] kindig, butter prints and molds, 86.

[6] kindig, butter prints and molds, 89

[7] kindig, butter prints and molds, 39.

thingiverse

free

19th Century Leather Children's Shoe: by smlee

...ttp://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers-detail.htm?soldierid=9ee02cbf-dc7a-df11-bf36-b8ac6f5d926a (accessed october 30, 2014).

Edenton

thingiverse

free

Tea Caddy used at the Edenton Tea Party in 1774 by hrmoll13

...e: edenton, chowan, north carolina, usa

dimensions: [lt] [wdt]3 11/16" [ht]5 5/16" [dt]1 3/4"

materials: porcelain

cg_trader

$10

FURNISHED 2 BASINS SDB EDENTON houses the world

...n houses the world

cg trader

furnished 2 basins sdb edenton houses the world 3d model, available formats max obj 3ds fbx stl dae

3dwarehouse

free

ESUMC Youth Group

...esumc youth group 3dwarehouse youth group building at edenton united methodist...

3dwarehouse

free

Wall mounted Bathroom Faucet

...wall mounted bathroom faucet 3dwarehouse based on: mirabelle edenton 1.2 gpm wall mounted faucet with single lever...

3dwarehouse

free

30 x 60 Bath Tub with Shower Doors

...with shower doors 3dwarehouse 30 x 60 bath mirabelle edenton tub with shower doors left and right versions...

3dwarehouse

free

MEUBLE SDB 2 VASQUES EDENTON, Maisons du monde. Réf: 138984 prix1 199,00

...sque #jaspea #maisons_du_monde #marbles #marbre #meuble_double_vasque_évier #persiennes #sala_de_baño #salle_de_bain #white #wood

3dwarehouse

free

meuble vasque, maisons du monde, ref 139602 prix 699,90

...votre salle d'eau. découvrez aussi le meuble double vasque edenton ce produit fait partie de la gamme ostende :...

1774

turbosquid

$12

human-1774

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model human-1774 for download as on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1163788)

3d_export

$10

among us characters rigged

...manual rigged. characters are lowpoly and each character has 1774 poly. characters are provided in a variety of colors....

3d_export

$36

Glass Award Trophy Shapes - crystal plaque trophies set

...4 - 2944 polygons, 2954 vertices;<br>-glass award 5 - 1774 polygons, 1778 vertices;<br>-glass award 6 - 11854 polygons, 11857...

thingiverse

free

Tea Caddy used at the Edenton Tea Party in 1774 by hrmoll13

...e: edenton, chowan, north carolina, usa

dimensions: [lt] [wdt]3 11/16" [ht]5 5/16" [dt]1 3/4"

materials: porcelain

sketchfab

$5

Palmse Distillery

...but the first stone distillery was raised already in 1774 the present bulky building with its 33-meter chimney was...

3dbaza

$4

Oleandro Chair Calligaris (319474)

...calligaris<br>version: 2017<br>preview: no<br>units: millimeters<br>dimension: 693.46 x 587.31 x 920.64<br>polys: 1774lt;br>verts: 1896<br>xform: yes<br>box trick: yes<br>model parts: 2<br>render: vray<br>formats: 3ds max...

thingiverse

free

Ulmer Schachtel ( 1/120th -- 15mm )

...and "the mysteries of free masonry" by william morgan (17741826) are all true. prague and hrad houska are important...

thingiverse

free

GY-63 Button Discrip by shivinteger

...#1 : 15622 + number of faces #2 : 1774 = 17396 [!] number of faces of union: 17529...

cg_trader

$15

ring-1774 | 3D

...4 | 3d

cg trader

ring-1774 3d print model ring engagement wedding gold platinum, available in 3dm, ready for 3d animation and ot

Caddy

turbosquid

$10

scissor caddy

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

3d_ocean

$89

Volkswagen Caddy 2011

... real car base. model is created accurately, in real units of measurement, qualitatively and maximally close to the original. ...

3d_export

$3

bath caddy tray for tub

...bath caddy tray for tub

3dexport

bath caddy tray for tub

turbosquid

$25

Chashaku and Tea caddy

...alty free 3d model chashaku and tea caddy for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1197555)

3d_export

$99

Volkswagen Caddy 2011 3D Model

...addy van 2011 2012 2013 2014 pickup commercial cab suv minivan mpv bus vw

volkswagen caddy 2011 3d model humster3d 39333 3dexport

turbosquid

$10

Wood Garden Caddy

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$5

Oblivion Tool Caddy

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

cg_studio

$37

VW caddy TDI3d model

...vw caddy tdi3d model

cgstudio

.max - vw caddy tdi 3d model, royalty free license available, instant download after purchase.

cg_studio

$37

VW caddy SDI3d model

...man car vehicles vehicle transport

.max - vw caddy sdi 3d model, royalty free license available, instant download after purchase.

3d_export

$39

Volkswagen Caddy 2021 wheel

...volkswagen caddy 2021 wheel

3dexport

Tea

3d_ocean

$5

Tea Can

...tea tea can tea canister tea pack tea packaging

tea canister, can, in different 3d formats. this one was created in 3ds max 2012.

design_connected

$18

Tea

...tea

designconnected

sancal tea computer generated 3d model. designed by ferrero, estudihac, jose manuel.

3d_export

$5

tea glass

...tea glass

3dexport

tea glass.

turbosquid

$1

Tea

...osquid

royalty free 3d model turkish tea for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1453029)

3ddd

$1

Tea set

...tea set

3ddd

сервиз

tea set

3d_export

free

Tea cup

...tea cup

3dexport

plastic tea cup

turbosquid

$1

TEA

...

royalty free 3d model tea for download as obj, 3ds, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1606404)

turbosquid

$1

Tea

...

royalty free 3d model tea for download as max, obj, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1620630)

turbosquid

$22

Tea

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

3d_ocean

$5

Tea Table

...tea table

3docean

interior tea.table

tea table for interior purposes

Party

design_connected

$13

Party

...party

designconnected

almerich party computer generated 3d model. designed by arnau, ramon.

3d_export

free

party chair

...party chair

3dexport

party chair

3d_ocean

$15

Party Bus

...r lebedev low poly lowpoly marge model party bus render rig simpsons the simpsons

party bus,modeled and textured in cinema4d r16.

turbosquid

$50

Party Room

...bosquid

royalty free 3d model party room for download as skp on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1284237)

turbosquid

free

Party chair

...e 3d model party chair for download as 3ds, max, obj, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1479188)

turbosquid

$45

Party Tent_4

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$39

Cofee Party

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$16

party cake

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$10

Party Train

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$1

Party Strobe

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

Used

3ddd

$1

US flag

...us flag

3ddd

флаг

us flag

3d_export

free

Among us

...among us

3dexport

among us red

3d_export

free

Among Us

...character from the game "among us". it can be used as a toy or...

3d_export

$6

among us

...among us

3dexport

doll from among us in red

3d_export

$5

amoung us

...amoung us

3dexport

amoung us character. was created by cinema 4d 19

3d_export

$5

Humvee us

...humvee us

3dexport

humvee us 3d model good quality for animation

3d_export

$15

among us

...among us 3dexport turbosmooth modifier can be used to increase mesh resolution if...

3d_export

$25

mailbox us

...mailbox us

3dexport

low poly model mailbox us. modeling in the blender, texturing in substance painter

design_connected

$13

Use Me

...use me

designconnected

sitland use me computer generated 3d model. designed by paolo scagnellato.

3d_export

$5

Among Us

...rt

the among us model comes in a variety of colors that can be customized by anyone, and even works with little in the animation