Thingiverse

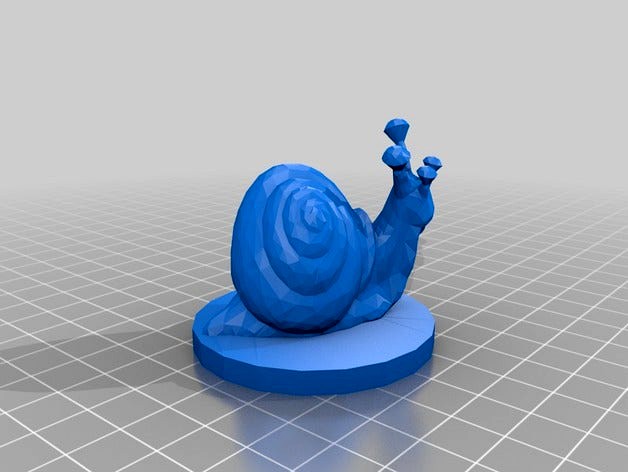

Emerald Flail Snail Monster for Tabletop Games by jawsnoir

by Thingiverse

Last crawled date: 3 years ago

Of all the bizarre creatures that haunt the caves and crevasses of the subterranean world, the flail snail is one of the strangest. As slow for its size as its diminutive cousins, the flail snail fears little from underground predators, thanks to its nigh-impermeable armor and the powerful, mace-like pseudopods that give it its name. Yet the most curious trait of this docile denizen lies is in the singular properties of its shell, which not only defends the creature against magic, but is capable of warping spells and flinging them back at their caster.

Slow and easily avoidable due to their telltale slime trails, flail snails tend to be peaceful unless actively threatened or approached too closely. At these times, the sedately waving tentacles on the creature’s head become an intricately woven blur, the horn-like growths at their tips whistling as they’re flung with terrific force by long strands of muscle. Each swipe of these biological flails is capable of staving in a man’s chest, and though most creatures have plenty of time to retreat, those who press their luck or run afoul of the flail snail’s mucilaginous secretions come out the other side as a red smear on the cavern floor.

The average flail snail stands 8 feet high at the top of its shell and 12 feet long, though the highly elastic nature of its flesh allows it to stretch out much farther. When threatened by an opponent not easily dispatched by its whirling tentacles, the flail snail can retract its entire body into its massive spiral shell, plugging the opening with its four rock-hard flails. These shells are frequently streaked with bright colors in patterns that differ between individuals; older snails tend to have larger shells with more elaborate markings, some of which may appear to resemble runes or symbols. Adult flail snails can weigh several thousand pounds, yet thanks to their slime they still manage to cling perfectly to the stone floors, walls, and even ceilings where they graze, feeding their prodigious bulk on fields of fungus, mold, and vermin. Though they have occasionally been known to consume carrion and the corpses of creatures they kill, this is generally believed to be due to lack of discrimination rather than malice, with the snail simply eating whatever it passes over out of habit.

Physically, flail snails differ from their lesser kindred only in their size, magical shells, and powerful antennae. Movement is achieved via a single enormous foot that takes up most of the underside of the snail’s body and pulls it along by expanding and contracting in muscular ripples aided by slimy secretions. Most of the snail’s day is spent eating with the help of a radula, a long ribbon of tongue studded with thousands of tiny tooth-like structures that act like a rasp, scraping organic matter from the stone and shredding it into pieces for digestion. The constant need to eat leads the snails to migrate frequently, either alone or in slow-moving colonies called routs, and any cavern or dungeon with sufficient organic matter growing on the walls is prime real estate to a flail snail, regardless of what any other inhabitants might think.

Like other slugs and snails, the tentacle-like protrusions on the flail snail’s head are its primary sensory organs, with the top pair sensing light and the lower providing the sense of smell and handling most tactile and fine manipulation duties. Both pairs can be retracted up to the horny growths at the end, and regrow in a month if lost. Even without these sensors, the snail can still move about reasonably well, as its suction with the ground allows it to sense its surroundings via tremors in the rock. This is especially useful since striking out with its powerful flails leads to them being easily damaged in combat.

Though the flail snail’s shell gets the most attention from adventurers and scholars, its slime trail is even more important to its defense and daily life. Like many other gastropods, the flail snail’s slime comes in two types: thin and slippery or thick and sticky. Both are effective at stopping those seeking to invade the snails’ territory, and allow the snails enough suction to climb walls and ceilings without faltering. Mixing the two even allows the snails to create a sticky rope capable of suspending them in the air, lowering themselves or climbing back up with astonishing ease.

Flail snails are born from clutches of up to 30 eggs stuck to cavern walls or buried beneath interesting objects (such as altars or lost treasure hordes). Fully hermaphroditic, flail snails begin their courtship ritual by extruding long, chitinous spears that they stab into each other’s flesh, injecting hormones signaling their intent. They then climb as a pair to the highest point available and begin copulating, lowering their entwined bodies on a massive rope of slime and hanging there for hours or days until mating is finished, at which point they may be forced to gnaw off their own reproductive organs in order to separate. Both individuals then lay egg clutches, and the hatchlings—which start out already shelled, the size of a human’s hand—are raised by the community, with no concept of lineage or heredity. Any flail snail sensing a hatchling in danger instantly rushes to its defense, regardless of personal peril. Matings happen sporadically and may be tied to available food sources, though the fact that flail snails appear to be able to live for hundreds or thousands of years makes reproduction a relatively rare occurrence. Under duress, flail snails have even been observed to retract into their shells and go into long periods of hibernation, making it possible that some of the snails currently active are far older than anyone realizes.

Of course, no discussion of the flail snail’s ecology would be complete without mention of its shell. A magnificent spiral construction several inches thick, the flail snail’s shell grows slowly over time, generated by an organ on the snail’s back known as its mantle, which in turn is fed by metals and minerals scraped in tiny amounts from the stone and ingested as part of the snail’s diet. The wide array of substances used to produce the shell appears to be at least partially responsible for the whorls of color and strange patterns that cover it, though the fact that these often glow after being targeted by magic suggests other factors as well.

Exactly how the shell manages to reflect magic has long baffled scholars, who have put forth numerous theories. Some suggest that it’s due to the ingestion and combination of various magically reactive metals used in the shell’s construction. Others posit that the shell is a focus for the snail’s own magical energies, and that by the whim of gods or evolution the snail has been restricted to using its powers in a retributive manner, an example of perfect natural balance. Still others maintain that the snail’s shell resonates with magic like a bell, acting as a sort of magical tuning fork whose vibration scatters the waves of energy. Perhaps the most compelling argument is that it’s not the shell’s composition that is key, but rather its shape. This theory holds that the flail snail shell has evolved in a perfect golden spiral, a shape long significant to arcanists and engineers, and that this shape manages to draw magic down into its center and then expel it again in a new direction, like a whirlpool or tornado.

Slow and easily avoidable due to their telltale slime trails, flail snails tend to be peaceful unless actively threatened or approached too closely. At these times, the sedately waving tentacles on the creature’s head become an intricately woven blur, the horn-like growths at their tips whistling as they’re flung with terrific force by long strands of muscle. Each swipe of these biological flails is capable of staving in a man’s chest, and though most creatures have plenty of time to retreat, those who press their luck or run afoul of the flail snail’s mucilaginous secretions come out the other side as a red smear on the cavern floor.

The average flail snail stands 8 feet high at the top of its shell and 12 feet long, though the highly elastic nature of its flesh allows it to stretch out much farther. When threatened by an opponent not easily dispatched by its whirling tentacles, the flail snail can retract its entire body into its massive spiral shell, plugging the opening with its four rock-hard flails. These shells are frequently streaked with bright colors in patterns that differ between individuals; older snails tend to have larger shells with more elaborate markings, some of which may appear to resemble runes or symbols. Adult flail snails can weigh several thousand pounds, yet thanks to their slime they still manage to cling perfectly to the stone floors, walls, and even ceilings where they graze, feeding their prodigious bulk on fields of fungus, mold, and vermin. Though they have occasionally been known to consume carrion and the corpses of creatures they kill, this is generally believed to be due to lack of discrimination rather than malice, with the snail simply eating whatever it passes over out of habit.

Physically, flail snails differ from their lesser kindred only in their size, magical shells, and powerful antennae. Movement is achieved via a single enormous foot that takes up most of the underside of the snail’s body and pulls it along by expanding and contracting in muscular ripples aided by slimy secretions. Most of the snail’s day is spent eating with the help of a radula, a long ribbon of tongue studded with thousands of tiny tooth-like structures that act like a rasp, scraping organic matter from the stone and shredding it into pieces for digestion. The constant need to eat leads the snails to migrate frequently, either alone or in slow-moving colonies called routs, and any cavern or dungeon with sufficient organic matter growing on the walls is prime real estate to a flail snail, regardless of what any other inhabitants might think.

Like other slugs and snails, the tentacle-like protrusions on the flail snail’s head are its primary sensory organs, with the top pair sensing light and the lower providing the sense of smell and handling most tactile and fine manipulation duties. Both pairs can be retracted up to the horny growths at the end, and regrow in a month if lost. Even without these sensors, the snail can still move about reasonably well, as its suction with the ground allows it to sense its surroundings via tremors in the rock. This is especially useful since striking out with its powerful flails leads to them being easily damaged in combat.

Though the flail snail’s shell gets the most attention from adventurers and scholars, its slime trail is even more important to its defense and daily life. Like many other gastropods, the flail snail’s slime comes in two types: thin and slippery or thick and sticky. Both are effective at stopping those seeking to invade the snails’ territory, and allow the snails enough suction to climb walls and ceilings without faltering. Mixing the two even allows the snails to create a sticky rope capable of suspending them in the air, lowering themselves or climbing back up with astonishing ease.

Flail snails are born from clutches of up to 30 eggs stuck to cavern walls or buried beneath interesting objects (such as altars or lost treasure hordes). Fully hermaphroditic, flail snails begin their courtship ritual by extruding long, chitinous spears that they stab into each other’s flesh, injecting hormones signaling their intent. They then climb as a pair to the highest point available and begin copulating, lowering their entwined bodies on a massive rope of slime and hanging there for hours or days until mating is finished, at which point they may be forced to gnaw off their own reproductive organs in order to separate. Both individuals then lay egg clutches, and the hatchlings—which start out already shelled, the size of a human’s hand—are raised by the community, with no concept of lineage or heredity. Any flail snail sensing a hatchling in danger instantly rushes to its defense, regardless of personal peril. Matings happen sporadically and may be tied to available food sources, though the fact that flail snails appear to be able to live for hundreds or thousands of years makes reproduction a relatively rare occurrence. Under duress, flail snails have even been observed to retract into their shells and go into long periods of hibernation, making it possible that some of the snails currently active are far older than anyone realizes.

Of course, no discussion of the flail snail’s ecology would be complete without mention of its shell. A magnificent spiral construction several inches thick, the flail snail’s shell grows slowly over time, generated by an organ on the snail’s back known as its mantle, which in turn is fed by metals and minerals scraped in tiny amounts from the stone and ingested as part of the snail’s diet. The wide array of substances used to produce the shell appears to be at least partially responsible for the whorls of color and strange patterns that cover it, though the fact that these often glow after being targeted by magic suggests other factors as well.

Exactly how the shell manages to reflect magic has long baffled scholars, who have put forth numerous theories. Some suggest that it’s due to the ingestion and combination of various magically reactive metals used in the shell’s construction. Others posit that the shell is a focus for the snail’s own magical energies, and that by the whim of gods or evolution the snail has been restricted to using its powers in a retributive manner, an example of perfect natural balance. Still others maintain that the snail’s shell resonates with magic like a bell, acting as a sort of magical tuning fork whose vibration scatters the waves of energy. Perhaps the most compelling argument is that it’s not the shell’s composition that is key, but rather its shape. This theory holds that the flail snail shell has evolved in a perfect golden spiral, a shape long significant to arcanists and engineers, and that this shape manages to draw magic down into its center and then expel it again in a new direction, like a whirlpool or tornado.

Similar models

free3d

free

Creature Snail w spikes on its shell V1

...creature snail w spikes on its shell v1

free3d

creature snail w spikes on its shell v1 printable, low poly model.

cg_trader

free

Snail

...animal gastropod spiral shellfish shell helix jungle invertebrate frog escargot crustacean rasp seafood animals other snail shell

thingiverse

free

Spool Snail by Intentional3D

...lime trail. the holder is designed for 4 cm wide spools and there are two models corresponding to spool diameters of 15 or 25 cm.

cg_trader

$5

low poly alien snail

... poly alien snail

cg trader

low poly alien snail made by blender alien snail scifi sea shell creature animals insect snail shell

3dwarehouse

free

Snail

...snail

3dwarehouse

a snail #animal #component #crawl #creature #eye #nature #nick #shell #sketchycat #snail #soft

grabcad

free

Flail(One-handed )

... flail features the classic flail design of a long wooden handle with a chain connected to its end, which supports a spiked ball.

unity_asset_store

$15

Casual Tiny Slime - Magic knight Pack

...casual tiny slime - magic knight pack asset from jj studio. find this & other creatures options on the unity asset store.

cg_trader

$8

snail 3d model

... lowpoly cartoon girl cartoon boy animals lion cartoon boy cartoon fish cartoon girl cartoon shark fish fish sea lion snail shell

thingiverse

free

flail snail

...ng made visit my instagram or patreon.

insta: www.instagram.com/homunculuscreations/

patreon: www.patreon.com/homunculuscreations

cg_trader

$50

Snail

... |frames| ) render ready! snail caracol caramujo molusco mollusk insect garden shell slow helix aspersa animals other snail shell

Jawsnoir

thingiverse

free

Efeeti Archer by jawsnoir

...jawsnoir

thingiverse

20mm medium sized efreeti archer for pathfinder or other tabletop games. extra spicey archer for your game.

thingiverse

free

Clown Wizard for Table Top Gaming by jawsnoir

...lown wizard for table top gaming by jawsnoir

thingiverse

22mm scale wizard clown with spooky ice cream cone for tabletop gaming.

thingiverse

free

Camel for Tabletop Gaming by jawsnoir

...get within 10 feet. the target must make a dc 13 fortitude save or be sickened for 1d4 rounds. the save dc is constitution-based.

thingiverse

free

War Bull for Tabletop Gaming by jawsnoir

... for warfare, driving them into enemy formations to break the front line or crush foot archers and other lightly armored targets.

thingiverse

free

Old PC Business Card Holder by jawsnoir

...ot;i remember when computers looked like this," tell the world even more by slapping some custom text or logo on the screen.

Flail

3d_ocean

$8

Flail

...ike and a round spike version. include a silver, gold and wood materials and textures. for any question nicomorin2002@homtail.com

turbosquid

$19

Flail

...

royalty free 3d model flail for download as ma, obj, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1405644)

turbosquid

$25

flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$20

Flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$20

flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$10

flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$8

Flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$5

Flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$2

Flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$5

Spike Flail

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

Snail

3d_export

$5

Snail

...snail

3dexport

snail modeling and stylization.

archibase_planet

free

Snail

...snail

archibase planet

snail picturesque element helix

snail - 3d model (*.gsm+*.3ds) for interior 3d visualization.

archibase_planet

free

Snail

...snail

archibase planet

snail helix insect

snail n020408- 3d model (*.gsm+*.3ds) for interior 3d visualization.

archibase_planet

free

Snail

...snail

archibase planet

snail helix cameo-shell

snail - 3d model (*.gsm+*.3ds) for exterior 3d visualization.

3d_ocean

$15

Snail

...u can turn stretchy body on or off . it ’ s work very well for tvc work or any kind of animation project.thanks for your support.

turbosquid

$25

Snail

...nail

turbosquid

royalty free 3d model snail for download as on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1257027)

turbosquid

$75

Snail

...l

turbosquid

royalty free 3d model snail for download as obj on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1513151)

turbosquid

$15

Snail

...l

turbosquid

royalty free 3d model snail for download as stl on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1669262)

turbosquid

$25

snail

...squid

royalty free 3d model snail for download as ma and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1483396)

turbosquid

$3

Snail

...squid

royalty free 3d model snail for download as ma and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1254926)

Tabletop

archibase_planet

free

Tabletop

...tabletop

archibase planet

rostrum platform stage

tabletop lecturn- 3d model for interior 3d visualization.

3ddd

$1

Tabletop Washbasin

...tabletop washbasin

3ddd

tabletop

modern design of tabletop washbasin

3d_export

$5

TABLETOP GREENHOUSE

...tabletop greenhouse

3dexport

tabletop greenhouse with accessories

turbosquid

free

Tabletop Decor

...urbosquid

free 3d model tabletop decor for download as blend on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1634208)

3ddd

$1

Mika White Tabletop

...mika white tabletop

3ddd

mika white tabletop ventless ethanol fireplace

turbosquid

$20

tabletop radio

...d model tabletop radio for download as 3ds, max, obj, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1167277)

turbosquid

free

Tabletop Sign

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

archive3d

free

Tabletop 3D Model

...odel

archive3d

rostrum platform stage

tabletop lecturn- 3d model for interior 3d visualization.

3ddd

free

Bench Vise Clamp Tabletop

...bench vise clamp tabletop

3ddd

тиски

bench vise clamp tabletop

turbosquid

$10

Ivanhoe Tabletop Lamp

... ivanhoe tabletop lamp for download as max, obj, fbx, and stl on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1411186)

Emerald

turbosquid

$19

Emerald

...yalty free 3d model emerald for download as max, obj, and fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1291181)

turbosquid

$9

Emerald

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$1

Emerald

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

turbosquid

$1

Emerald

... available on turbo squid, the world's leading provider of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games.

3d_export

free

Emerald

...ds max. rendering v-ray 5. textures often work after rendering, but in this case, it’s better to write that there are no textures

3ddd

$1

Emerald Сhair

...emerald сhair

3ddd

emerald

в архиве есть файл 2012.maxhttp://www.di-gallerie.com/shop/94/desc/emerald-shair

design_connected

free

Emerald Mirror

...emerald mirror

designconnected

free 3d model of emerald mirror by baker designed by pheasant, thomas.

3ddd

$1

emerald

...emerald

3ddd

emrald , cattelan italia

зеркало emrald cattelan italia

turbosquid

$45

Emerald ring

...squid

royalty free 3d model emerald ring for download as 3dm on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1198430)

turbosquid

$19

Emerald Ring

...squid

royalty free 3d model emerald ring for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1234448)

Monster

3d_export

$5

monster

...monster

3dexport

very realistic monster

3d_export

free

monster

...monster

3dexport

bloody monster! (looks terrifying)

3d_ocean

$12

Monster

... this code “envatoguest2016” . visit our store high details 3d character model for small monster , useful for animations, movi...

3d_ocean

$15

Monster

...monster

3docean

android game ios java main model monster playdesign

polycount :1118 texture :1024×1024png

3d_ocean

$8

Monster Man

...monster man

3docean

giant monster

monster man software: 3ds max, mental ray.

turbosquid

$60

MONSTER

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model monster for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1220728)

turbosquid

$60

Monster

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model monster for download as fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1320840)

turbosquid

$19

Monster

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model monster for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1248452)

turbosquid

$15

Monster

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model monster for download as max on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1293042)

turbosquid

$15

Monster

...turbosquid

royalty free 3d model monster for download as ztl on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1417804)

Games

3d_ocean

$4

Games

...games

3docean

3d games models real stick

3d, models, sports, games , trail

turbosquid

$5

Games

...s

turbosquid

royalty free 3d model games for download as skp on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1612115)

turbosquid

$25

Game

...of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games ...

turbosquid

$10

Game

...of digital 3d models for visualization, films, television, and games ...

turbosquid

$5

Game

...for download as blend on turbosquid: 3d models for games architecture, videos....

3d_ocean

$7

game place

...game place

3docean

children game game park game place kids play luna park play

for kids game place

3d_export

$14

game character

...game character

3dexport

game character use for gaming

turbosquid

$20

Game Ready Car For Video Games

...e 3d model game ready car for video games for download as fbx on turbosquid: 3d models for games, architecture, videos. (1499375)

3d_ocean

$5

Game fence

...game fence

3docean

fence game

a high quality game ready fence.

3d_ocean

$16

Arcade Game

...tomate button coin computer console fun game gamer gaming joystick machine play side art video game

detailed arcade game machine.